[First posted June 27, 2011 based on multiple dpreview posts Jan 13, 2009. Copyright Øivind Tøien]IntroductionNikon DSLRs are generally specified with an operating temperature down to 0°C (32°F). Does that mean that they stop working and break below that temperature? No, it just means that Nikon (and others manufactures) are conservative in their specifications. There might be components inside that are only specified down to 0°C although they will keep working at lower temperatures, thus the whole device needs to be specified with that tolerance. So how low can they go in a practical situation, and what does the photographer need to care about?

Cold can affect the proper operation of a DSLR in a number of principal ways:

1) Condensation problems

2) Battery performance

3) Mechanical /electronic issues

4) Ability of the photographer to operate it in the cold

Read on to find out about each of them.

1) Condensation problems. The ability of air to hold humidity varies with temperature; the warmer the air, the more water vapor it can hold on to. While relative humidity tells us how close the air is to being saturated, the dew point of the air is a much more useful variable for us here as it will tell how cold an object can be before humidity in the air may condensate on the object. Thus

low temperature in itself is not what causes condensation, it is when a) our camera equipment is colder than the dew point of the atmosphere around it or b) that the inside surface of the equipment get colder than the dew point of the air contained within it.

a) An example where surface condensation may form is a situation where the camera has been used outside so that its surface temperature has dropped to -20°C. We

then go inside a modern airtight house with bathrooms and perhaps a air humidifier to keep musical instruments healthy - the dew point may be as high as +5°C. Frost will then quickly build up on all outside surfaces of the equipment, and then melt as the equipment warms up. Another similar example is however the opposite situation: You live in an air conditioned house in coastal North Carolina. Inside temperature is a cool 18°C. Outside temperature is 35°C, nearly saturated, so dew point is up at 32°C. We go

from inside to outside and condensation water will immediately form on the surface. The remedy in both cases is to let the gear acclimatize before exposure to the new environment. One often see Ziploc plastic bags recommended, however they will also prevent humidity that have been trapped, for instance snow on the camera, from escaping. Usually

all that is needed to prevent condensation problems is just letting the camera warm up in the closed camera bag for a good while after coming from a cold to warm place.b) Condensation on inside surfaces of equipment could theoretically happen when going from a warm humid to a colder place. In practice temperature changes inside the camera happens slowly, and there is little air space and some humidity may have a chance to escape (weather sealed professional equipment being worse in this respect…). Thus signs of condensation inside will often be more of a sign that water has penetrated into the equipment at some point. The exception might be very humid warm tropical climates where desiccants will be your friend when storing the gear.

In general, condensation problems in a really cold climate like Fairbanks, Alaska where I live is much less of a problem than most think because the cold air has so little capacity to hold humidity and air inside buildings (sourced from the outside) is usually very, very dry. Most photographers traveling to cold places worry too much about condensation. And quite frankly, a little surface condensation on your DSLR is not likely to kill it, just wipe it off as soon as it melts and go on.

2) Battery performance in the cold is affected in two different ways.a) The battery’s efficiency and thereby effective capacity decreases in the cold. Bjørn (nfoto) did an excellent systematic test of ENEL3e Lithium-ion batteries in his D200 review (

http://www.naturfotograf.com, down on the main page), and found that they did not loose much capacity (about 15%) at -5°C, which is according to my own observations. Down below -20°C things are starting get a bit worse, but see below.

The battery’s voltage output decreases when temperature drops. Even without being used the battery status will indicate lower and lower apparent charge when the battery is cooling, until it may finally show depleted and the body stops working. The Li-Ion batteries appear to be more strongly affected by this below –25°C, and when they reach -40°C they all appear dead.

This is usually a reversible effect; re-warm the battery in your shirt pocket and it magically regains its apparent capacity.So the remedy for battery problems in the cold is simple:

always carry one or more spare Li-Ion batteries that are kept in a warm place near your body while the other battery is being used.Another but expensive alternative in extreme cold is to use non-rechargeable Lithium AA batteries if your camera body can accept that. They have remarkable performance even at -40°C (lower specification).

3) Mechanical and electronic issues in the cold – how low can they go? Living in interior Alaska where cold spells of -40°C are pretty common, one quickly learns that below a certain temperature, (typically -30°C), mechanical things are starting to act weird. So how do the Nikon bodies do at these more extreme temperatures? Do they work at all? As an example, during a long cold spell I set up a simple test: I left my different Nikon bodies outside at about -40°C for 9-10 hours. The bodies were my trusty F2 that participated in countless of winter camping trips in Norway without problems but never much below -30°C, my F4 with 4 non-rechargeable lithium batteries, my then 3 year old D200 and 1 year old D40x, both with fully charged warm batteries inserted before powering and trying to release the shutter. With the digital bodies and F4 the tests were repeated another night.

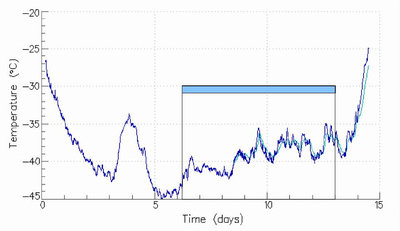

Here is a temperature record from data loggers at the test site, starting Dec. 29. The bar shows the period of testing with temperatures of about -40°C. The dark blue is outside temperature, and the light blue is temperature next to where I hid the cameras, a site which was somewhat temperature buffered. (Recording with the data logger started somewhat late and the first half of the recording is estimated from a recording station in a couple of miles away).

I expected that the mechanical F2, the F4 and possibly D200 would pass the test, but it was quite opposite.

In all of these bodies, the mirror would not go all the way up, confirmed visually by releasing shutter without lens (holding breath…) and in the D200 also by the presence of scary frames like this (blockage is because the secondary mirror did not raise much):

It did not take much warm-up for the D200 to start to recover, and after a little more warming (and also helped by lens pointing upwards), it was completely recovered. From this, my estimate is that the limit of the D200 when equilibrated to ambient temperature was between -30 to -35°C, which is in accordance with feedback I have got from other photographers regarding similar models.

The F4 powered up without battery change, and after warm-up the mirror started working normally again.

The F2 locked completely up and could not be advanced again before the mirror was pushed up manually (and I discovered that after it had been several weeks in locked-up state…).

And then the surprise:

D40x, the consumer model just kept on exposing frame after frame without a hitch. All it needed was to swap in a fresh warm battery, and it just kept going. I did repeat this test after two years on the D200 and the D40x at slightly higher temperature (-36°C) with the same results, so age was probably not an issue with these two, the F4 and F2 had not been serviced for about 20 years though…

D -40 xtreme ?

So what was going on here? With the reservation that there is only one sample tested of each camera and performance in extreme cold is often unpredictable, one thing that distinguishes the D40x from the others is that it is a simpler cheaper construction, and perhaps with less lubricant and more plastic used. Another difference might be the construction of the mirror mechanism. I believe the two film bodies and the D200 all use a spring loaded mirror opposed to the D40x which uses a motor, implied in an intervju with Kazunari Orii, Deputy Manager Nikon,

http://imaging.nikon.com/history/scenes/26/index_02.htm : “in Nikon's high-end models, we use a spring instead of a motor to raise the mirror.” Thus it is possible that the spring was not strong enough to overcome the increased friction at low temperature and raise the mirror all the way up, spring force being weakest at the top, while the motor would keep going until the mirror was raised.

The test result was surprising as I have used my D200 at -40°C a number of times before, and sometimes been out for hours in slightly less cold conditions and have not had any other problem than the need to feed it warm batteries.

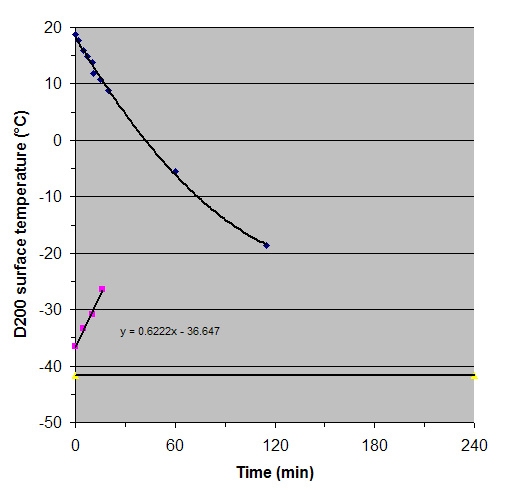

Why do I not see the problems in practical use as in the test? Let us look at a cooling curve in a typical situation in a padded case: I taped a thermocouple wire (a very small temperature sensor) to my D200, placed it in my Thinktank Digital Holster 20 out in the cold at an initial ambient temperature of -41.7°C (thick horizontal line in graph below) and checked the D200 temperature with a digital readout now an then:

The cooling is quite slow; it took 2 hours to reach to two thirds of the final temperature. Extrapolating (it was late, I needed to sleep…), 4h total will probably only result in a temperature of -34°C which means that on most trips under these conditions the camera would never be equilibrated to ambient temperature. (4 hours at -41°C is a long time for photographer even with good clothing). Digital cameras may also be helped keeping warm when operating by heat production in electronic components like the display/sensor/processing board. Initial warming rate at room temperature of a cold camera in the bag (purple) was about the same as the initial cooling rate.

A further test with a D200 first equilibrated to room temperature and then exposed on a tripod at -38°C, using the timer to take one exposure every 5 min and occasional manual checks for low battery gave the following result: First battery lasted 40 min before it got too cold. Second battery (inserted after a 10 min lapse into the cold body) lasted 20min. With the third warm battery in, problems with the mirror started at 80 min (bottom of frame dark).

Other things that did not work: On both DSLRs the viewfinder LCD including focus brackets became almost unreadable (slow) after a night at -40°C; having programmed a center press on the multiselector of the D200 to center the focus point is very helpful. Top LCD was also extremely slow. Opposed to this, the TFT based LCD on the back of both bodies was quite readable and just a bit slow. Having exposure data displayed there on the D40x was very useful. Both bodies recovered completely when rewarmed.

Lenses: The AFS 18-55mm (non-VR II) kit lens’ zoom mechanism completely jammed after moving it a tiny bit from 35mm toward 55mm! AF and MF worked reasonably well. So as a single focal length lens it is usable if zoom setting is decided beforehand… After warming up again everything worked as normal.

The focus on AIS lenses (28/2.8 AIS, 105/2.5 AIS, 105/4 AIS micro) got very stiff when equilibrated to about -40°C, but workable. Just do not expect to follow a fast subject. On AF lenses (AF 20/2.8, AF 60/2.8 micro AF300 f/4) the manual focus did not get quite that stiff, and the AF worked on the D200 although slow. Aperture setting and depth of field preview on the camera with AF(S) and AIP lenses (28mm) worked, but aperture was difficult to read on the D200 top display and viewfinder displays. My AFS 12-24/4 has only seen a few hours at a time below -30°C, and has then worked without problems.

I contacted Rich at Alaska Camera Repair here in Fairbanks for comment. He gets lots of calls from worried photographers each winter who is coming up to cover the Iditarod Sled Dog Race. He was also surprised that the D40x did that well, and F2 did not do better. Old mechanical cameras are supposed to be very reliable; he said FM2 was one of the best in the cold. Graphite for winterizing cameras has not been used for a long time (would not want that in a digital body!). If winterizing is done it is more about removing lubrication at the cost of some extra wear. He also has some extremely thin oil. It did not sound like it is done often on digital SLR's these days as it is not needed much.

Could performance be improved by keeping the camera warm beneath clothing? Well, the body may release humidity into the clothing layers, and that could cause condensation, so it is probably not a good idea (in addition to problems with fitting a large DSLR under an anorak/jacket). There is however always exceptions: I have personally had no problems with keeping a compact camera in an inside pocket, and since it is kept fairly warm and is outside for short moments at a time there is little chance of condensation. It is usually the only way to keep those small batteries going. A photographer living in Point Barrow in Northern Alaska informed me that he kept his D3 warm beneath his parka without condensation problems. The parka is quite loose and allows dry air to circulate through it. (And people up there are usually getting around on a snow machine, not skiing which may cause more moisture release.)

4) Ability of the photographer to operate the DSLR in the cold.Metal camera parts quickly conduct heat away from fingers and other body parts. During my cold testing above I once or twice forgot to put on my face mask before checking my D200 right outside my door. The result was a frost bite on the nose tip, so be warned! Cold fingers do of course not operate small camera controls well. To keep the circulation going in peripheral parts of the human body, it is essential to keep central parts warm enough so that our body will dump excess heat to the hands, feet and face. A trick I often use if I start exercising and cannot get the peripheral circulation going in spite of starting to get warm centrally is to stop exercising for a minute or so to allow priority of circulation to hands and feet over exercising muscles.

Small plastic camera bodies like D40x and lenses with plastic barrels have clear advantages when operated with bare hands in the cold as they conduct less heat. However a small camera body is difficult or impossible to operate with thick mittens (I often use 3 layers of wool inside a shell), which then has to come off. Many of the most essential functions on my D200 can be operated without taking the mittens off. Equipment like tripod legs can be insulated with foam or cork tape (I use the one designed for bicycle handlebars).

Surviving and being comfortable at -40°C is a matter of being prepared before going outside and have proper clothing (especially peripheral parts) and footwear. Just a small detail like not lashing the boots too tight can make the difference between warm and dangerously cold toes. There is also a factor of adaptation. After a cold spell at -50°C it feels very comfortable when it warms up to -40! Visitors from warmer areas that come up here during winter can feel a bit miserable because their skin is more sensitive to cold (read pain) in the beginning which causes constriction of blood vessels in the skin that makes it even worse. You can tell from the white face versus the red face of an Alaskan. Underneath a face mask though there can be almost tropical conditions. With all the clothes on it is so hard to move so that one barely needs a tripod :~). Getting comfortable with wearing all those clothes is an important part of the adaptation.

Actually the biggest problem with operating a camera in more extreme cold is the photographers own breathing. Frost deposits will easily block a clear view through the viewfinder eyepiece and cause fogging when it get to the front element/filter of the lens or ice fog from the breath drifts in the air in front of it. Some good control of breathing is called for. And although others may disagree, most of the times in the cold I prefer to have an NC filter on the lens from which I can wipe frost deposits or snow with means that are not optimal for cleaning a front element... If it gets too clogged, the filter can then be removed for another chance without filter.

5) ConclusionsI think the overall conclusion here is that Nikon DSLRs are surprisingly tough even in pretty extreme cold as long as the Li-ion batteries are swapped with warm ones. What limits the use of the camera in the cold is usually the photographer’s ability to stay warm enough to operate the equipment, see and make decisions rather than the equipment itself. Keeping the camera insulated in a bag when not used slows the cooling curve so that the apparent operating temperature is lower than static cold tests should indicate. Only for outdoor life like winter camping and expeditions in very cold regions or leaving it outside in a sled or deep frozen car during a cold spell would one expect the static limits of the DSLRs cold tolerance to come into effect. Down to -30°C professional models are even then probably not going to encounter problems, although things may slow down a bit. I am less sure about consumer models, more sloppy tolerances could possibly cause more variability between each single body; we need some more data to see if my D40x is just a very lucky one. I have gotten some different feedback on this matter. Data need to include information on both temperatures, duration, to what degree it was insulated in a bag and battery swaps. Cheap kit lenses may also potentially face problems that could partially spoil the party. If long term exposure to temperature below -30-35°C is expected, testing of specific equipment is recommended before critical use.

Opposed to this dry cold, wet-cold and stormy weather is expected to cause none of the issues seen during the deep freeze and will put other properties like weather sealing more to test. And finally: May be you should not tell Nikon you used your camera at -33°C when you send it in for warranty service…

For those who wonder what those low temperatures look like, here are some examples.Caribou digging in the snow North of Brooks Range at about -40°C , D200, AF 300mm f/4. (Inversion layers forming in low areas can disturb long lens use, especially if you are just at the altitude of the transition layer and shoot though it) :

Frosty fur, Muskox at -43°C, F4 and AF 20mm f/2.8:

Animals still need to be fed when it drops below -40°C. Nikon F4 200mm f/4:

Ice fog over landscape at -50°C. Nikon F4, old scan:

Ice fog from human activity at -40°C, D40x 28mm f/2.8 AIS :

New years firework with ice fog at -40°C, D200 28mm f/2.8 AIS. Some watched it from their car…

All images copyright 1998-2009 Øivind Tøien

[In the following post I will recall some of the resulting discussions and provide some updates.]